Indiana University Athletics

Gold Standard: Knight Assembles Team to Remember in '84

4/6/2020 7:15:00 AM | Men's Basketball

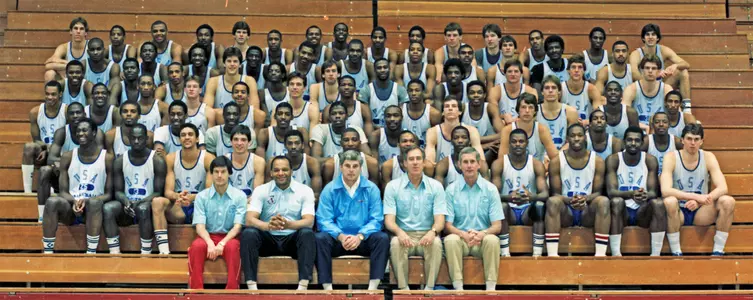

Thirty-three years ago, arguably the United States' greatest amateur basketball team was assembled in Bloomington.

The architect of that team was Indiana University head coach Bob Knight. In 1984 Knight was at the forefront of the college basketball scene, 13 seasons and two national titles into an IU coaching career that would span an additional 15 seasons and added another national crown. That success made him a logical choice for USA Basketball when it tabbed him to select and coach a team that would play on home soil in the summer of 1984 at the Olympic Games in Los Angeles.

Knight welcomed 73 of the country's best to Bloomington in April of 1984, all fighting for 12 roster spots. Many of those players – some of whom didn't make the team - would eventually become household names. Michael Jordan. Karl Malone. Patrick Ewing. Charles Barkley. John Stockton.

"As the team formed, you could tell it was a pretty special group," says Tim Garl, IU's Head Men's Basketball Trainer who served in that same role on the '84 U.S. team. "They bonded, got close, and had fun as a group. But they were also a team on a mission. And coach never let them forget that."

Thirty-three years later, reminders from those Trials remain in Bloomington. Indiana University Athletics passed along hundreds if not thousands of action photos from practices and scrimmages to Indiana University Archives. There are also scores of statistical sheets from those same scrimmages which helped decide the make-up of a team that would eventually win its eight contests at the Los Angeles Games by an average of 32 points on its way to the gold medal.

Perhaps most interesting, though, are a handful of one-page, typewritten sheets with notes on various players. Those notes, according to Garl, are from Knight.

***

The numbered comments broke down the player's efforts and performances on both ends of the court, and included anywhere from 18 to 30 observations on various players who were competing for a spot on the team.

One player's notations included 24 comments, all of which were critical. A few of those notes:

"1. Loses sight of ball – Doesn't help on post.

"8. No stance – poor post defense – foolish foul.

"21. Drifts into occupied post instead of popping out to wing for spacing."

Of course, with 73 players invited to the Trials, there were bound to be some that weren't up to Knight's standards. That must explain these comments about a player, right?

Those comments were Knight's about Michael Jordan, the then-University of North Carolina standout who would go on to win six NBA Championships, five league MVPs and lay claim to the moniker of greatest player in the history of the game.

Thoughts on another player:

"3. Kills dribble and can't improve passing angle.

"7. Throws ball to baseline with no purpose.

20. Doesn't use dribble to take ball to the shooter."

Those comments were about a then little-known guard from Gonzaga – John Stockton – who would go on to become the NBA's all-time leader in assists.

And Knight's take on a third player:

"4. Lack of defensive alertness.

"7. Slow defensive recovery – poor defense to the ball.

"19. Just walks across the lane – doesn't look for screening action to initiate offense."

That player? Georgetown center Patrick Ewing, who would go on to rank in the top 25 in NBA history in scoring, rebounding and blocked shots.

Another player who didn't make the final roster also drew a critical take from Knight:

"3. Poor defensive stance, no passing lane pressure, no testing stance.

"11. Forces a bad shot, has open men post at the free-throw line.

"23. Dribbles into trouble instead of waiting to see if the post man is open coming off the cross screen."

Those thoughts were on Auburn forward Charles Barkley, who would go on to earn first- or second-team All-NBA honors ten times and one NBA MVP award.

Finally, a fifth player whose inability to get open offensively drew critical thoughts from Knight:

"1. Drifts – stands – doesn't set up cuts.

4. Doesn't screen anybody – doesn't make hard cuts to get open.

"17. Doesn't make hard cuts – easy to guard."

That player? Knight's own Hoosier standout, then-freshman guard Steve Alford. Alford was one of the Big Ten's all-time great shooters and led IU in scoring in each of his four seasons. As adept and efficient at using screens as any player the Big Ten has seen in recent memory, Alford owned the school's all-time scoring record (2,438 points) before it was eclipsed by Calbert Cheaney in 1993.

It's important to note that Knight's comments didn't indicate a failed assessment of each player's abilities. Jordan and Ewing were both selected to the team and were first and third, respectively, on the team in scoring. The fourth-leading scorer on that team was Alford, who averaged 10.3 points per contest.

Barkley, meanwhile, admitted he shouldn't have been named to the team because he was more focused on the start of his NBA career. Like Stockton, Barkley made the initial cuts and was in the final 20 before ultimately missing the team.

"That's the way it went (with Knight)," Garl says. "I may have sent a copy of those (notes) to Jordan, kind of a joke, to say hey, these were some notes Coach had on you."

***

That results of Knight's approach can't be disputed. Five of Team USA's eight wins were by at least 30 points, including a 96-65 win over Spain in the Gold Medal contest. Every win came by double digits as Knight's squad inserted itself as a formidable opponent to the 1960 Team USA squad (Jerry West, Walt Bellamy, Jerry Lucas, Ocar Robertson) in a discussion of the greatest amateur basketball teams the United States has ever assembled.

While that moniker wasn't a focus of Knight's, winning the gold medal was once the Hoosier coach was tabbed to lead the '84 team.

"The thought of getting beat was unthinkable," Garl says. "Coach is such a patriot, and (former Vanderbilt Coach and Team USA assistant coach) C.M. (Newton), and the other coaches were similar in that regard.

"The thought of anything other than winning the gold never entered their heads."

While the U.S.'s route to the gold medal wasn't necessarily considered a foregone conclusion before the Olympics got underway, the absence of one team was well noted. Following the United States' decision to boycott the 1980 Olympic Games in Moscow, the Soviet Union did the same in 1984. The Arvydas Sabonis-led team from the U.S.S.R. was expected to be Team USA's stiffest competition in 1984 before the boycott.

But Knight wasn't about to let the absence of the Soviet squad lessen his team's accomplishment. And he wasn't shy about voicing his opinion on whether the Soviet team could have threatened his team for the gold medal. After all, Knight's Team USA squad had not only convincingly won the gold medal, but had also gone unbeaten in a series of exhibition games against a number of NBA All-Star teams that included the likes of Larry Bird, Magic Johnson and Isiah Thomas during their preparation for the Summer Games.

But Knight wasn't about to let the absence of the Soviet squad lessen his team's accomplishment. And he wasn't shy about voicing his opinion on whether the Soviet team could have threatened his team for the gold medal. After all, Knight's Team USA squad had not only convincingly won the gold medal, but had also gone unbeaten in a series of exhibition games against a number of NBA All-Star teams that included the likes of Larry Bird, Magic Johnson and Isiah Thomas during their preparation for the Summer Games.

Several months after the Games concluded, the Soviet National team came to Bloomington for an exhibition game before the start of IU's 1984-85 season. When Knight greeted long-time Soviet National Coach Alexander Gomelsky before the game, he had a gift – and some words – for the long-time coach.

"Coach's gift to him was a pair of Air Jordan basketball shoes," Garl says. "And his remark to him was 'we would have beaten you anytime, anyplace with the 1984 team.'"

As Knight's gesture would suggest, that 1984 team was clearly led by Jordan, the 1984 Naismith College Basketball Player of the Year who averaged a team-best 17.1 points/game during the Olympic contests. His dominance was clear throughout the Trials; a cumulative statistical sheet of the team's intra-squad games thru July 6, 1984, showed Jordan easily led the team in field goals (176, Sam Perkins ranked second with 124) and field goal attempts (315, Perkins was second with 224) and his 38 steals ranked second only to Alvin Robertson's 53.

But as good as Jordan was, no one necessarily expected him to become the game's all-time best. His jump shot was considered by many to be a liability, and his college career had recently ended at the hands of, of all teams, Knight's Indiana squad. The Hoosiers held Jordan to 13 points in a 72-68 upset win over the top-ranked Tar Heels in the 1984 NCAA Regional semifinals.

"I don't think many were saying this was going to be the greatest player in the history of basketball," says Jim Butler, who in 1984 was an employee of WTTV-Channel 4 in Bloomington and the producer of the Bob Knight TV Show.

Butler had been with Channel 4 since 1977, initially working as a cameraman on the Bob Knight TV Show before becoming the producer of IU Football Coach Lee Corso's TV Show in 1978. In 1984 the producer for The Bob Knight Show left the TV station, and Butler moved into that role in the spring.

Knight's TV show aired throughout the Olympic Trials, giving Butler an opportunity to witness the tryouts in Bloomington and to travel with the team for a series of games in California before the Olympics got underway. It was during one of those games that Butler said he saw Jordan do something that he can't necessarily describe, because he wasn't entirely sure of what he saw.

"He made a play in one of those games that was almost indescribable – he drove the baseline, got trapped, was cut off," Butler said. "It then it looked to me like he dematerialized on one side of the defender, and then rematerialized on the other side and then dunked.

"I had never seen anything like that in my life. At that point I thought, this guy is going to be pretty good."

***

NBA teams agreed that Jordan had a chance to be special, which is why he decided to leave North Carolina after his junior season and declare for the 1984 NBA Draft. The professional draft was held on June 19, just days before Knight made the final cuts to 12 players (from 16) for the U.S. Olympic squad.

Today, the NBA Draft is a spectacle. It airs on national television in primetime. Players, families, coaches and friends are all in attendance, along with thousands of fans who have spent months debating whom their favorite NBA franchise should select and pay tens of millions of dollars.

That wasn't the case in 1984.

Virtually all of the draft-eligible players who remained at the U.S. Olympic Trials in Bloomington were expected to be selected early in the '84 draft (ultimately, 11 of the team's 12 players were first-round selections in either 1984 or 1985). But none '84 eligible players departed Bloomington for the event; instead they went through their regular routine in Bloomington prior to the draft, which took place at Madison Square Garden's Felt Forum.

The draft was broadcast by the USA Network, which arranged with WTTV to do a live feed from Bloomington as the participants in the Trials were selected. Once they were drafted, they were led into the WTTV studio, where local television staff attached a microphone and fed questions to the players from the USA Network director in New York.

That afforded Butler another unforgettable memory, as he spent the afternoon and evening with those players while they waited to discover their NBA fate.

"It was one of the best moments of my life," Butler said. "This took the whole afternoon to do, and after the first couple of interviews I left the studio and went to the (TV station's) lobby and just hung out with the guys.

"At one point I'm there just hanging out talking with Michael Jordan, Leon Wood, guys like that. What a thrill."

By the time the first round had concluded, eight of the first 18 selections had been players who remained in contention for a spot on the U.S. Olympic squad – Jordan (selected 3rd), Perkins (4th), Robertson (7th), Lancaster Gordon (8th), Wood (10th), Tim McCormick (12th), Jeff Turner (17th) and Vern Fleming (18th). A year later, five of the top seven picks in the 1985 NBA Draft were members of the '84 Olympic squad – Patrick Ewing (1st), Wayman Tisdale (2nd), Jon Koncak (5th), Joe Kleine (6th) and Chris Mullin (7th).

Butler remembers a couple of funny exchanges with Wood in the WTTV lobby as the '84 draft unfolded. Wood was selected by the Philadelphia 76ers, a team that had also taken U.S. Olympic Trial casualty Charles Barkley with the fifth overall pick.

"Wood says, 'Oh man, I'm going to the 76ers, and that's where Charles is,'" Butler recalls. "'Charles is going to get all their money!'"

An outgoing personality from Cal-State Fullerton, Wood also poked some fun at Team USA teammate Vern Fleming, a point guard from Georgia whom Butler described as tremendously shy at the time. Fleming was taken 18th in the 1984 NBA Draft by the Indiana Pacers, who had gone an NBA-worst 26-56 in the recently-completed 1983-84 season.

"Leon would say, 'Alvin (Robertson), where you going?' Oh, San Antonio," Butler recalls. "He'd ask all the other guys the same question.

"Then he got to Vern. 'Vern, where you going? Indiana? Where? Oh, Vern. I'm sorry. I'm so sorry."

Ultimately, there was nothing for Wood to be sorry about – Fleming spent 11 of his 12 years in the NBA with the Pacers and still ranks among the franchise's all-time leaders in scoring (eighth), assists (second), steals (third) and games played (third). The Pacers advanced to the playoffs seven times during Fleming's career, including trips to the Eastern Conference Finals in each of his final two seasons in Indianapolis.

Wood, meanwhile, lasted only six years in the league, averaging 6.4 points for six different teams. He's now in his 22nd year as an NBA referee.

--

By the time the 1984 NBA Draft had concluded and the players left the WTTV studio, eight of the 16 players still under consideration for the U.S. squad had their lives changing significantly. Jordan's initial contract included a $1 million signing bonus as part of a five-year, $6 million deal. Even the last of the U.S. Olympic Trials participants selected – Fleming – was set to earn $200,000 in his rookie season.

But according to Garl, Knight managed to keep the players' focus on Los Angeles and the quest for a gold medal.

"Coach didn't deny (the Draft) happened," Garl said. "But he said, 'hey, you need to do the Olympic thing first. We have a job to do.'"

Knight's message was heard, and the team's focus didn't waiver. Shortly after the NBA Draft, Knight cut the final four players – Lancaster Gordon, Johnny Dawkins, Chuck Person and Tim McCormick – on June 27 to get the roster down to the final 12. From there the team embarked on a coast-to-coast tour of exhibition games in preparation for the Olympics. Included was a July 9 match-up against NBA All-Stars at the Hoosier Dome in Indianapolis that drew 67,596 fans – a total that established a new record for the largest crowd to ever witness a basketball game.

"A game in July in the heat and humidity of summer draws 67,596 fans? Where else but Indiana?" says IU Assistant Athletic Director Chuck Crabb, who served as the public address announcer at the game and later as the Press Center Interview Manager at the Los Angeles Games.

***

Team USA rolled through its competition once it arrived in Los Angeles. Robertson scored 18 to lead the team to a 48-point win over China in its opener. Jordan, Ewing and Alford then led Team USA in scoring in the next three games as the squad continued to demolish its foes in group play, easily qualifying them for the medal round.

Team USA rolled through its competition once it arrived in Los Angeles. Robertson scored 18 to lead the team to a 48-point win over China in its opener. Jordan, Ewing and Alford then led Team USA in scoring in the next three games as the squad continued to demolish its foes in group play, easily qualifying them for the medal round.

The team's quarterfinal opponent – West Germany – proved to be the stiffest competition during the Games, pushing Team USA before falling, 78-67. The West German team featured not only future NBA standout Detlef Schrempf, but also Hoosier junior Uwe Blab, who scored 10 points against Knight's U.S. squad.

The biggest thing Team USA had to overcome in that game, though, wasn't Schrempf or Blab, but a bad tooth. Garl said that Jordan had been dealing with a toothache before the game, something they kept quiet.

"I took him to the dentist and they worked on him a little bit and we went back to workouts, and afterwards he was still hurting," Garl said. "So I took him back and they ended up doing an extraction. So he had a tooth pulled before the game and didn't play that well (Jordan had 14 points and a game-high six turnovers). No one ever said anything about the tooth."

With the tooth gone and the West Germans dispatched, Team USA proceeded to whip Canada in the semifinals by 21 to set up a Gold Medal match-up with Spain.

On the court, there was little drama in the championship game, as Team USA cruised to a 99-65 win to claim the gold medal. The nervous moments, though, came before the game when the squad was warming up.

"It's one of the great stories that people have probably never heard of," said Garl.

Throughout the Games, Team USA's players and staff stayed in the Olympic Village on the University of Southern California campus. Depending on traffic, the USC campus was a 20-30 minute drive from men's basketball venue, The Forum in Inglewood.

As the team was warming up for the Gold Medal game, Garl noticed a problem – underneath his warm-up, Jordan was wearing the wrong color uniform. Since the players dressed before heading over to the game, Jordan's white jersey was back in his room in the Olympic Village.

The staff immediately sprang into action. Team USA assistant and Dayton University coach Don Donoher grabbed a sheriff's officer and the pair raced back to the USC campus. Garl, meanwhile, phoned the dormitory and told a close friend who was a member of the medical staff about the situation and instructed him to tell security to let him into Jordan's room so he could grab his white jersey, and then he was instructed to and it off to Donoher and the officer in the lobby.

That plan would have succeeded if not for one small issue.

"I hadn't had a chance to tell Donoher they'd have the jersey in the lobby waiting for him," Garl said.

So the security officer goes into Jordan's room, they get the jersey, and they return to the lobby. Donoher, meanwhile, races through the lobby and up to Jordan's room. He tears through Jordan's belongings, unable to find the correct uniform.

As Donoher is searching for the jersey, the member of the medical staff with the jersey grew nervous, as he knew game time was approaching.

"He ends up grabbing another officer and says, 'hey, we got to go,'" Garl said. "They have to have this to start the game."

So the trainer and the second officer race through Los Angeles and Olympic traffic to The Forum, arriving in time for Jordan to switch uniforms before tip-off. Soon afterwards, Donoher returns and heads to Garl.

"He's like, 'I searched everywhere, high and low, that jersey wasn't there,'" Garl said. "I said, 'Don, I'm sorry, we had it all set, you missed each other in the lobby, and they panicked and drove out here and we got it resolved.'"

That near miss did little to distract Jordan or the team before they took the court against Spain. In the final moments before the team took the court for the gold medal game, Knight did what he traditionally did for all games – he began writing the offensive and defensive priorities on the locker room chalkboard. As he was writing Jordan interrupted his pre-game ritual.

"Jordan said, 'Coach, never mind this, we're ready to play,'" Garl recalls. "It's not necessary."

It wasn't – Jordan scored 20 points to lead Team USA to the 99-65 win.

***

It was a team that will forever hold its own among the great amateur basketball teams ever assembled. While there always would have been a special place in the hearts of Hoosiers for the squad thanks to the presence of Alford on the roster and Knight on the sidelines, the decision to hold the Olympic Trials in Bloomington makes it even more special.

According to Garl, that was a decision Knight made, and it ran contrary to the norm of taking players to the U.S. Olympic Committee headquarters in Colorado Springs, Col. But there was no pushback from USA Basketball.

"The guys at the head of USA Basketball said it's your team, we don't want to present any obstacles or give you any problems," Garl said. "They didn't want anyone to have any regrets."

So with that decision cleared, 73 players and many of the nation's premier college coaches descended on Bloomington in April of 1984. The players stayed at the IU Memorial Union, and Garl still has the original rooming list (one of the more interesting roommate tandems on the alphabetized list was Barkley and Alford). Among those who stayed at the Union was Garl, who offered up his house to members of the coaching staff to use.

It created a very special environment in Bloomington, according to Crabb.

"You had all of basketball's attention on Bloomington," Crabb said.

While the pursuit of the gold medal was the focus of both players and coaches during their Bloomington stays, Knight didn't prevent the players from getting around town. The city was well-versed in the sport of college basketball, and the players were celebrities once they ventured away from the practice courts and mingled with the members of the community.

"(The players) found Ye Old Regulator, they found Nick's," Crabb recalls. "They enjoyed what night life there is in Bloomington."

That was particularly true during off days. In an era long before cell phones, Garl recalls a time or two when he needed to find a player on an off day, but was unable to locate them in their Memorial Union hotel room. Left with no other options, he'd enlist a manager to track them down.

And where would they find the players?

"I'd send a manager down to Nick's, and more often than not, they could find some of the guys there," Garl said.

Proof of the players' presence remains to this day. At Nick's, several signed the wall in the hallway that leads to the "Hump" room on the establishment's top floor. Among those players was Joe Kleine, who included this saying with his signature:

"If the beers cold, we'll win the gold."

While the players bounced around town when the opportunity presented itself, the coaching staff followed Knight's lead and were rarely seen around town. When the coaching staff headed out to eat, they'd often go to a private dining area in a back room of Smitty's, a long-since departed local dining establishment on the corner of Walnut Street and Hillside Drive that Knight often frequented.

"They'd eat every southern Indiana fat food delicacy there was and just have a ball," Crabb said.

The coaches also spent many long hours in and around Assembly Hall and the IU Fieldhouse, which was the headquarters during the early part of the Trials in April when all 73 players remained. With 10 courts set-up inside the Fieldhouse, Knight and other coaches sat atop a forklift where they could watch all of the games from one location.

When the day's games would end, the staff would retreat to the IU locker room to discuss which players would make up the U.S. squad.

In that locker room, according to Garl, was a new state-of-the-art side-by-side refrigerator donated by one of Bloomington's biggest employers at the time, RCA. Making sure things were in it, meanwhile, was the responsibility of former IU basketball manager Steve Skoronski.

"Steve's major responsibility was to make sure the right kind of beer was in the fridge," Garl said. "He had to make sure he had a little bit of everything because you had so many coaches. They didn't all drink beer, but Steve had to make sure if someone wanted something in particular that it was there, otherwise he was running to Big Red to go get it."

When Garl ventured into the locker room during those coaches' sessions, he remembers it was a Who's Who of big names in the college game. In addition to Knight, Donoher and Newton, George Raveling, Gene Keady, Mike Krzyzewski, Digger Phelps, Henry Iba and Pete Newell were among the other coaching legends or legends-to-be that were sharing their thoughts and bantering back and forth.

"They all took it seriously, but I also remember a lot of laughing and a lot of storytelling," Garl said. "I'm sure if you'd ask any of them they'd remember that time very fondly, having a lot of peers together like that"

That group of coaches, led by Knight, assembled a team that basketball fans remember fondly as well, one that cemented itself as one of the country's all-time best on the amateur level.

And how couldn't they? After all, it had a scoring machine in Jordan who would go on to win 10 NBA scoring titles.

"Poor spacing – stays next to man," Knight noted about Jordan.

And the team had a defensive stopper in the backcourt in Alvin Robertson, a standout at Arkansas who would go on to win NBA Defensive Player of the Year honors in his second year in the league and still owns the NBA record for most steals/game in a career.

"Poor stance, gets turned on screen, loses track of the ball and man," Knight wrote.

Offensively, Chris Mullin was versatile inside-outside forward who was a three-time Big East Conference Player of the Year and ended up playing for 16 years in the NBA.

"Does not get set to shoot, could use a shot fake."

And in the post, the team had Ewing, arguably the most intimidating defensive defender the college game has seen in the last 40 years.

"Doesn't take away step into lane – no blockout," Knight wrote.

Who could find anything wrong with that team?

The architect of that team was Indiana University head coach Bob Knight. In 1984 Knight was at the forefront of the college basketball scene, 13 seasons and two national titles into an IU coaching career that would span an additional 15 seasons and added another national crown. That success made him a logical choice for USA Basketball when it tabbed him to select and coach a team that would play on home soil in the summer of 1984 at the Olympic Games in Los Angeles.

Knight welcomed 73 of the country's best to Bloomington in April of 1984, all fighting for 12 roster spots. Many of those players – some of whom didn't make the team - would eventually become household names. Michael Jordan. Karl Malone. Patrick Ewing. Charles Barkley. John Stockton.

"As the team formed, you could tell it was a pretty special group," says Tim Garl, IU's Head Men's Basketball Trainer who served in that same role on the '84 U.S. team. "They bonded, got close, and had fun as a group. But they were also a team on a mission. And coach never let them forget that."

Thirty-three years later, reminders from those Trials remain in Bloomington. Indiana University Athletics passed along hundreds if not thousands of action photos from practices and scrimmages to Indiana University Archives. There are also scores of statistical sheets from those same scrimmages which helped decide the make-up of a team that would eventually win its eight contests at the Los Angeles Games by an average of 32 points on its way to the gold medal.

Perhaps most interesting, though, are a handful of one-page, typewritten sheets with notes on various players. Those notes, according to Garl, are from Knight.

***

The numbered comments broke down the player's efforts and performances on both ends of the court, and included anywhere from 18 to 30 observations on various players who were competing for a spot on the team.

One player's notations included 24 comments, all of which were critical. A few of those notes:

"1. Loses sight of ball – Doesn't help on post.

"8. No stance – poor post defense – foolish foul.

"21. Drifts into occupied post instead of popping out to wing for spacing."

Of course, with 73 players invited to the Trials, there were bound to be some that weren't up to Knight's standards. That must explain these comments about a player, right?

Those comments were Knight's about Michael Jordan, the then-University of North Carolina standout who would go on to win six NBA Championships, five league MVPs and lay claim to the moniker of greatest player in the history of the game.

Thoughts on another player:

"3. Kills dribble and can't improve passing angle.

"7. Throws ball to baseline with no purpose.

20. Doesn't use dribble to take ball to the shooter."

Those comments were about a then little-known guard from Gonzaga – John Stockton – who would go on to become the NBA's all-time leader in assists.

And Knight's take on a third player:

"4. Lack of defensive alertness.

"7. Slow defensive recovery – poor defense to the ball.

"19. Just walks across the lane – doesn't look for screening action to initiate offense."

That player? Georgetown center Patrick Ewing, who would go on to rank in the top 25 in NBA history in scoring, rebounding and blocked shots.

Another player who didn't make the final roster also drew a critical take from Knight:

"3. Poor defensive stance, no passing lane pressure, no testing stance.

"11. Forces a bad shot, has open men post at the free-throw line.

"23. Dribbles into trouble instead of waiting to see if the post man is open coming off the cross screen."

Those thoughts were on Auburn forward Charles Barkley, who would go on to earn first- or second-team All-NBA honors ten times and one NBA MVP award.

Finally, a fifth player whose inability to get open offensively drew critical thoughts from Knight:

"1. Drifts – stands – doesn't set up cuts.

4. Doesn't screen anybody – doesn't make hard cuts to get open.

"17. Doesn't make hard cuts – easy to guard."

That player? Knight's own Hoosier standout, then-freshman guard Steve Alford. Alford was one of the Big Ten's all-time great shooters and led IU in scoring in each of his four seasons. As adept and efficient at using screens as any player the Big Ten has seen in recent memory, Alford owned the school's all-time scoring record (2,438 points) before it was eclipsed by Calbert Cheaney in 1993.

It's important to note that Knight's comments didn't indicate a failed assessment of each player's abilities. Jordan and Ewing were both selected to the team and were first and third, respectively, on the team in scoring. The fourth-leading scorer on that team was Alford, who averaged 10.3 points per contest.

Barkley, meanwhile, admitted he shouldn't have been named to the team because he was more focused on the start of his NBA career. Like Stockton, Barkley made the initial cuts and was in the final 20 before ultimately missing the team.

"That's the way it went (with Knight)," Garl says. "I may have sent a copy of those (notes) to Jordan, kind of a joke, to say hey, these were some notes Coach had on you."

***

That results of Knight's approach can't be disputed. Five of Team USA's eight wins were by at least 30 points, including a 96-65 win over Spain in the Gold Medal contest. Every win came by double digits as Knight's squad inserted itself as a formidable opponent to the 1960 Team USA squad (Jerry West, Walt Bellamy, Jerry Lucas, Ocar Robertson) in a discussion of the greatest amateur basketball teams the United States has ever assembled.

While that moniker wasn't a focus of Knight's, winning the gold medal was once the Hoosier coach was tabbed to lead the '84 team.

"The thought of getting beat was unthinkable," Garl says. "Coach is such a patriot, and (former Vanderbilt Coach and Team USA assistant coach) C.M. (Newton), and the other coaches were similar in that regard.

"The thought of anything other than winning the gold never entered their heads."

While the U.S.'s route to the gold medal wasn't necessarily considered a foregone conclusion before the Olympics got underway, the absence of one team was well noted. Following the United States' decision to boycott the 1980 Olympic Games in Moscow, the Soviet Union did the same in 1984. The Arvydas Sabonis-led team from the U.S.S.R. was expected to be Team USA's stiffest competition in 1984 before the boycott.

But Knight wasn't about to let the absence of the Soviet squad lessen his team's accomplishment. And he wasn't shy about voicing his opinion on whether the Soviet team could have threatened his team for the gold medal. After all, Knight's Team USA squad had not only convincingly won the gold medal, but had also gone unbeaten in a series of exhibition games against a number of NBA All-Star teams that included the likes of Larry Bird, Magic Johnson and Isiah Thomas during their preparation for the Summer Games.

But Knight wasn't about to let the absence of the Soviet squad lessen his team's accomplishment. And he wasn't shy about voicing his opinion on whether the Soviet team could have threatened his team for the gold medal. After all, Knight's Team USA squad had not only convincingly won the gold medal, but had also gone unbeaten in a series of exhibition games against a number of NBA All-Star teams that included the likes of Larry Bird, Magic Johnson and Isiah Thomas during their preparation for the Summer Games.Several months after the Games concluded, the Soviet National team came to Bloomington for an exhibition game before the start of IU's 1984-85 season. When Knight greeted long-time Soviet National Coach Alexander Gomelsky before the game, he had a gift – and some words – for the long-time coach.

"Coach's gift to him was a pair of Air Jordan basketball shoes," Garl says. "And his remark to him was 'we would have beaten you anytime, anyplace with the 1984 team.'"

As Knight's gesture would suggest, that 1984 team was clearly led by Jordan, the 1984 Naismith College Basketball Player of the Year who averaged a team-best 17.1 points/game during the Olympic contests. His dominance was clear throughout the Trials; a cumulative statistical sheet of the team's intra-squad games thru July 6, 1984, showed Jordan easily led the team in field goals (176, Sam Perkins ranked second with 124) and field goal attempts (315, Perkins was second with 224) and his 38 steals ranked second only to Alvin Robertson's 53.

But as good as Jordan was, no one necessarily expected him to become the game's all-time best. His jump shot was considered by many to be a liability, and his college career had recently ended at the hands of, of all teams, Knight's Indiana squad. The Hoosiers held Jordan to 13 points in a 72-68 upset win over the top-ranked Tar Heels in the 1984 NCAA Regional semifinals.

"I don't think many were saying this was going to be the greatest player in the history of basketball," says Jim Butler, who in 1984 was an employee of WTTV-Channel 4 in Bloomington and the producer of the Bob Knight TV Show.

Butler had been with Channel 4 since 1977, initially working as a cameraman on the Bob Knight TV Show before becoming the producer of IU Football Coach Lee Corso's TV Show in 1978. In 1984 the producer for The Bob Knight Show left the TV station, and Butler moved into that role in the spring.

Knight's TV show aired throughout the Olympic Trials, giving Butler an opportunity to witness the tryouts in Bloomington and to travel with the team for a series of games in California before the Olympics got underway. It was during one of those games that Butler said he saw Jordan do something that he can't necessarily describe, because he wasn't entirely sure of what he saw.

"He made a play in one of those games that was almost indescribable – he drove the baseline, got trapped, was cut off," Butler said. "It then it looked to me like he dematerialized on one side of the defender, and then rematerialized on the other side and then dunked.

"I had never seen anything like that in my life. At that point I thought, this guy is going to be pretty good."

***

NBA teams agreed that Jordan had a chance to be special, which is why he decided to leave North Carolina after his junior season and declare for the 1984 NBA Draft. The professional draft was held on June 19, just days before Knight made the final cuts to 12 players (from 16) for the U.S. Olympic squad.

Today, the NBA Draft is a spectacle. It airs on national television in primetime. Players, families, coaches and friends are all in attendance, along with thousands of fans who have spent months debating whom their favorite NBA franchise should select and pay tens of millions of dollars.

That wasn't the case in 1984.

Virtually all of the draft-eligible players who remained at the U.S. Olympic Trials in Bloomington were expected to be selected early in the '84 draft (ultimately, 11 of the team's 12 players were first-round selections in either 1984 or 1985). But none '84 eligible players departed Bloomington for the event; instead they went through their regular routine in Bloomington prior to the draft, which took place at Madison Square Garden's Felt Forum.

The draft was broadcast by the USA Network, which arranged with WTTV to do a live feed from Bloomington as the participants in the Trials were selected. Once they were drafted, they were led into the WTTV studio, where local television staff attached a microphone and fed questions to the players from the USA Network director in New York.

That afforded Butler another unforgettable memory, as he spent the afternoon and evening with those players while they waited to discover their NBA fate.

"It was one of the best moments of my life," Butler said. "This took the whole afternoon to do, and after the first couple of interviews I left the studio and went to the (TV station's) lobby and just hung out with the guys.

"At one point I'm there just hanging out talking with Michael Jordan, Leon Wood, guys like that. What a thrill."

By the time the first round had concluded, eight of the first 18 selections had been players who remained in contention for a spot on the U.S. Olympic squad – Jordan (selected 3rd), Perkins (4th), Robertson (7th), Lancaster Gordon (8th), Wood (10th), Tim McCormick (12th), Jeff Turner (17th) and Vern Fleming (18th). A year later, five of the top seven picks in the 1985 NBA Draft were members of the '84 Olympic squad – Patrick Ewing (1st), Wayman Tisdale (2nd), Jon Koncak (5th), Joe Kleine (6th) and Chris Mullin (7th).

Butler remembers a couple of funny exchanges with Wood in the WTTV lobby as the '84 draft unfolded. Wood was selected by the Philadelphia 76ers, a team that had also taken U.S. Olympic Trial casualty Charles Barkley with the fifth overall pick.

"Wood says, 'Oh man, I'm going to the 76ers, and that's where Charles is,'" Butler recalls. "'Charles is going to get all their money!'"

An outgoing personality from Cal-State Fullerton, Wood also poked some fun at Team USA teammate Vern Fleming, a point guard from Georgia whom Butler described as tremendously shy at the time. Fleming was taken 18th in the 1984 NBA Draft by the Indiana Pacers, who had gone an NBA-worst 26-56 in the recently-completed 1983-84 season.

"Leon would say, 'Alvin (Robertson), where you going?' Oh, San Antonio," Butler recalls. "He'd ask all the other guys the same question.

"Then he got to Vern. 'Vern, where you going? Indiana? Where? Oh, Vern. I'm sorry. I'm so sorry."

Ultimately, there was nothing for Wood to be sorry about – Fleming spent 11 of his 12 years in the NBA with the Pacers and still ranks among the franchise's all-time leaders in scoring (eighth), assists (second), steals (third) and games played (third). The Pacers advanced to the playoffs seven times during Fleming's career, including trips to the Eastern Conference Finals in each of his final two seasons in Indianapolis.

Wood, meanwhile, lasted only six years in the league, averaging 6.4 points for six different teams. He's now in his 22nd year as an NBA referee.

--

By the time the 1984 NBA Draft had concluded and the players left the WTTV studio, eight of the 16 players still under consideration for the U.S. squad had their lives changing significantly. Jordan's initial contract included a $1 million signing bonus as part of a five-year, $6 million deal. Even the last of the U.S. Olympic Trials participants selected – Fleming – was set to earn $200,000 in his rookie season.

But according to Garl, Knight managed to keep the players' focus on Los Angeles and the quest for a gold medal.

"Coach didn't deny (the Draft) happened," Garl said. "But he said, 'hey, you need to do the Olympic thing first. We have a job to do.'"

Knight's message was heard, and the team's focus didn't waiver. Shortly after the NBA Draft, Knight cut the final four players – Lancaster Gordon, Johnny Dawkins, Chuck Person and Tim McCormick – on June 27 to get the roster down to the final 12. From there the team embarked on a coast-to-coast tour of exhibition games in preparation for the Olympics. Included was a July 9 match-up against NBA All-Stars at the Hoosier Dome in Indianapolis that drew 67,596 fans – a total that established a new record for the largest crowd to ever witness a basketball game.

"A game in July in the heat and humidity of summer draws 67,596 fans? Where else but Indiana?" says IU Assistant Athletic Director Chuck Crabb, who served as the public address announcer at the game and later as the Press Center Interview Manager at the Los Angeles Games.

***

Team USA rolled through its competition once it arrived in Los Angeles. Robertson scored 18 to lead the team to a 48-point win over China in its opener. Jordan, Ewing and Alford then led Team USA in scoring in the next three games as the squad continued to demolish its foes in group play, easily qualifying them for the medal round.

Team USA rolled through its competition once it arrived in Los Angeles. Robertson scored 18 to lead the team to a 48-point win over China in its opener. Jordan, Ewing and Alford then led Team USA in scoring in the next three games as the squad continued to demolish its foes in group play, easily qualifying them for the medal round.The team's quarterfinal opponent – West Germany – proved to be the stiffest competition during the Games, pushing Team USA before falling, 78-67. The West German team featured not only future NBA standout Detlef Schrempf, but also Hoosier junior Uwe Blab, who scored 10 points against Knight's U.S. squad.

The biggest thing Team USA had to overcome in that game, though, wasn't Schrempf or Blab, but a bad tooth. Garl said that Jordan had been dealing with a toothache before the game, something they kept quiet.

"I took him to the dentist and they worked on him a little bit and we went back to workouts, and afterwards he was still hurting," Garl said. "So I took him back and they ended up doing an extraction. So he had a tooth pulled before the game and didn't play that well (Jordan had 14 points and a game-high six turnovers). No one ever said anything about the tooth."

With the tooth gone and the West Germans dispatched, Team USA proceeded to whip Canada in the semifinals by 21 to set up a Gold Medal match-up with Spain.

On the court, there was little drama in the championship game, as Team USA cruised to a 99-65 win to claim the gold medal. The nervous moments, though, came before the game when the squad was warming up.

"It's one of the great stories that people have probably never heard of," said Garl.

Throughout the Games, Team USA's players and staff stayed in the Olympic Village on the University of Southern California campus. Depending on traffic, the USC campus was a 20-30 minute drive from men's basketball venue, The Forum in Inglewood.

As the team was warming up for the Gold Medal game, Garl noticed a problem – underneath his warm-up, Jordan was wearing the wrong color uniform. Since the players dressed before heading over to the game, Jordan's white jersey was back in his room in the Olympic Village.

The staff immediately sprang into action. Team USA assistant and Dayton University coach Don Donoher grabbed a sheriff's officer and the pair raced back to the USC campus. Garl, meanwhile, phoned the dormitory and told a close friend who was a member of the medical staff about the situation and instructed him to tell security to let him into Jordan's room so he could grab his white jersey, and then he was instructed to and it off to Donoher and the officer in the lobby.

That plan would have succeeded if not for one small issue.

"I hadn't had a chance to tell Donoher they'd have the jersey in the lobby waiting for him," Garl said.

So the security officer goes into Jordan's room, they get the jersey, and they return to the lobby. Donoher, meanwhile, races through the lobby and up to Jordan's room. He tears through Jordan's belongings, unable to find the correct uniform.

As Donoher is searching for the jersey, the member of the medical staff with the jersey grew nervous, as he knew game time was approaching.

"He ends up grabbing another officer and says, 'hey, we got to go,'" Garl said. "They have to have this to start the game."

So the trainer and the second officer race through Los Angeles and Olympic traffic to The Forum, arriving in time for Jordan to switch uniforms before tip-off. Soon afterwards, Donoher returns and heads to Garl.

"He's like, 'I searched everywhere, high and low, that jersey wasn't there,'" Garl said. "I said, 'Don, I'm sorry, we had it all set, you missed each other in the lobby, and they panicked and drove out here and we got it resolved.'"

That near miss did little to distract Jordan or the team before they took the court against Spain. In the final moments before the team took the court for the gold medal game, Knight did what he traditionally did for all games – he began writing the offensive and defensive priorities on the locker room chalkboard. As he was writing Jordan interrupted his pre-game ritual.

"Jordan said, 'Coach, never mind this, we're ready to play,'" Garl recalls. "It's not necessary."

It wasn't – Jordan scored 20 points to lead Team USA to the 99-65 win.

***

It was a team that will forever hold its own among the great amateur basketball teams ever assembled. While there always would have been a special place in the hearts of Hoosiers for the squad thanks to the presence of Alford on the roster and Knight on the sidelines, the decision to hold the Olympic Trials in Bloomington makes it even more special.

According to Garl, that was a decision Knight made, and it ran contrary to the norm of taking players to the U.S. Olympic Committee headquarters in Colorado Springs, Col. But there was no pushback from USA Basketball.

"The guys at the head of USA Basketball said it's your team, we don't want to present any obstacles or give you any problems," Garl said. "They didn't want anyone to have any regrets."

So with that decision cleared, 73 players and many of the nation's premier college coaches descended on Bloomington in April of 1984. The players stayed at the IU Memorial Union, and Garl still has the original rooming list (one of the more interesting roommate tandems on the alphabetized list was Barkley and Alford). Among those who stayed at the Union was Garl, who offered up his house to members of the coaching staff to use.

It created a very special environment in Bloomington, according to Crabb.

"You had all of basketball's attention on Bloomington," Crabb said.

While the pursuit of the gold medal was the focus of both players and coaches during their Bloomington stays, Knight didn't prevent the players from getting around town. The city was well-versed in the sport of college basketball, and the players were celebrities once they ventured away from the practice courts and mingled with the members of the community.

"(The players) found Ye Old Regulator, they found Nick's," Crabb recalls. "They enjoyed what night life there is in Bloomington."

That was particularly true during off days. In an era long before cell phones, Garl recalls a time or two when he needed to find a player on an off day, but was unable to locate them in their Memorial Union hotel room. Left with no other options, he'd enlist a manager to track them down.

And where would they find the players?

"I'd send a manager down to Nick's, and more often than not, they could find some of the guys there," Garl said.

Proof of the players' presence remains to this day. At Nick's, several signed the wall in the hallway that leads to the "Hump" room on the establishment's top floor. Among those players was Joe Kleine, who included this saying with his signature:

"If the beers cold, we'll win the gold."

While the players bounced around town when the opportunity presented itself, the coaching staff followed Knight's lead and were rarely seen around town. When the coaching staff headed out to eat, they'd often go to a private dining area in a back room of Smitty's, a long-since departed local dining establishment on the corner of Walnut Street and Hillside Drive that Knight often frequented.

"They'd eat every southern Indiana fat food delicacy there was and just have a ball," Crabb said.

The coaches also spent many long hours in and around Assembly Hall and the IU Fieldhouse, which was the headquarters during the early part of the Trials in April when all 73 players remained. With 10 courts set-up inside the Fieldhouse, Knight and other coaches sat atop a forklift where they could watch all of the games from one location.

When the day's games would end, the staff would retreat to the IU locker room to discuss which players would make up the U.S. squad.

In that locker room, according to Garl, was a new state-of-the-art side-by-side refrigerator donated by one of Bloomington's biggest employers at the time, RCA. Making sure things were in it, meanwhile, was the responsibility of former IU basketball manager Steve Skoronski.

"Steve's major responsibility was to make sure the right kind of beer was in the fridge," Garl said. "He had to make sure he had a little bit of everything because you had so many coaches. They didn't all drink beer, but Steve had to make sure if someone wanted something in particular that it was there, otherwise he was running to Big Red to go get it."

When Garl ventured into the locker room during those coaches' sessions, he remembers it was a Who's Who of big names in the college game. In addition to Knight, Donoher and Newton, George Raveling, Gene Keady, Mike Krzyzewski, Digger Phelps, Henry Iba and Pete Newell were among the other coaching legends or legends-to-be that were sharing their thoughts and bantering back and forth.

"They all took it seriously, but I also remember a lot of laughing and a lot of storytelling," Garl said. "I'm sure if you'd ask any of them they'd remember that time very fondly, having a lot of peers together like that"

That group of coaches, led by Knight, assembled a team that basketball fans remember fondly as well, one that cemented itself as one of the country's all-time best on the amateur level.

And how couldn't they? After all, it had a scoring machine in Jordan who would go on to win 10 NBA scoring titles.

"Poor spacing – stays next to man," Knight noted about Jordan.

And the team had a defensive stopper in the backcourt in Alvin Robertson, a standout at Arkansas who would go on to win NBA Defensive Player of the Year honors in his second year in the league and still owns the NBA record for most steals/game in a career.

"Poor stance, gets turned on screen, loses track of the ball and man," Knight wrote.

Offensively, Chris Mullin was versatile inside-outside forward who was a three-time Big East Conference Player of the Year and ended up playing for 16 years in the NBA.

"Does not get set to shoot, could use a shot fake."

And in the post, the team had Ewing, arguably the most intimidating defensive defender the college game has seen in the last 40 years.

"Doesn't take away step into lane – no blockout," Knight wrote.

Who could find anything wrong with that team?

IUWBB Postgame vs. Ohio State (BTT)

Thursday, March 05

IUWBB Postgame vs. Nebraska (BTT)

Thursday, March 05

IUWBB Highlights vs. Nebraska (BTT)

Wednesday, March 04

IUBB Postgame Press Conference

Wednesday, March 04